The VC2 Victory Ship

The demand for the Victory ship class came out of a desire to correct two problems. The first problem was that the Liberty ship was too slow, in particular it could not be part of the high-speed convoy system.

Convoys crossing the Atlantic to Support Operation Overlord were categorised as either a fast convoy or a slow convoy. It was noticeable that losses from the slow convoys were significantly higher than the fast ones. The other problem was that though the C2 cargo ships could join the fast convoys it was felt they took too long to build.

The Victory ships were produced in large numbers by American shipyards in the second half of the war. They were a more modern design compared to the Liberty, they were slightly larger and had more powerful steam turbines giving a higher speed to allow participation in high speed convoys and make them more difficult targets for German U-boats. A total of 531 Victory ships were built between 1944 and 1946.

The design of the Victory ships commenced in 1942, the design was an enhancement of the Liberty ship which had already been successfully produced in extraordinary numbers. The Victory ships were slightly larger than the Liberty ships at 400 feet (139 m) long 1.8 m and 19 m wide and drawing 8.5 m fully loaded. Displacement was up just under 1,000 tons to 15,200 with a raised forecastle and more sophisticated deckhouse. Improved hull shape helped achieve the higher speed, they had quite a different appearance from the Liberty ships.

To make them less vulnerable to U-boat attacks, Victory ships made between 15 and 17 knots which was 4 to 6 knots faster than the Liberties. They also had a longer range. The extra speed was achieved through more modern efficient engines. Rather than the Liberties 2,500 horsepower triple-expansion steam engines, the Victory ships were designed to use steam turbines with outputs between six and eight and a half thousand horsepower. Another improvement was electrically powered auxiliary equipment rather than steam-driven machinery.

To prevent the hull cracks, that many Liberty ships had developed, the spacing between frames was widened from 30 inches to 36 inches making the ships less stiff and more able to flex. Like Liberty ships the hull was welded rather than riveted.

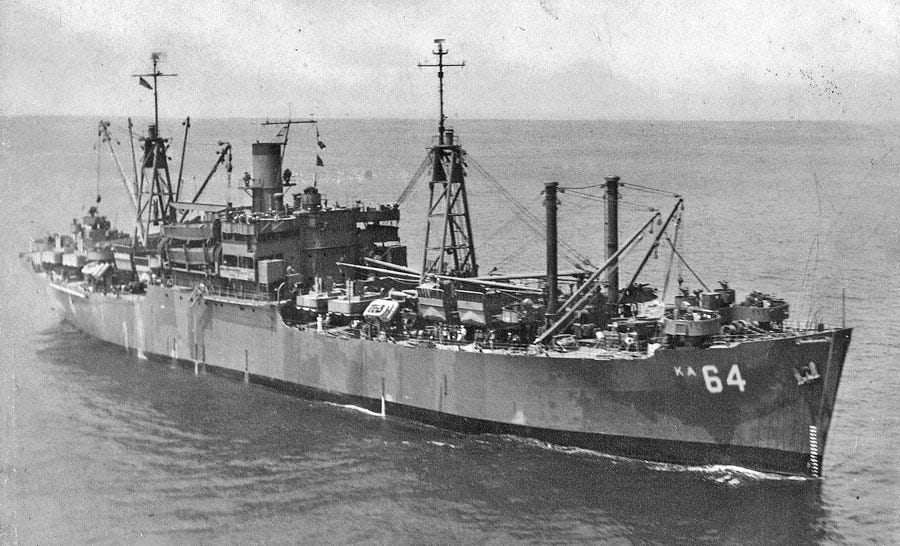

Of the wartime construction 414 were of the standard cargo variant and 117 were attack transports. The majority of them, 272 vessels, were the VC2–S–AP2 type with 6,000 hp C2 type machinery followed by 141 VC2–S–AP3 with 8,500 horsepower C3 type engines.

The attack transports were the C2–S–AP5 known as the Haskell class, they were designed to take troops and their equipment into battle. They were basically troop ships with a greatly enlarged crew complement of 535. They also had different cargo handling equipment. Up to 3,000 tons of heavy stores including vehicles could be stacked in the lower holds and up to 1,600 troops were carried in the twin decks. The foremasts were replaced by two kingposts that would normally have been at the front of the superstructure and the boat deck was extended over number three hatch forward and number four hatch aft. The extended boat deck was used to store up to 20 small landing craft. More landing craft could be accommodated over number two and number five hatches. The mainmast and topmast were extended and radio aerials were attached to the funnel. The lead ship Haskell was laid down in March 1944 and launched on the 13th of June.

Because the Atlantic battle had been won by the time the first of the Victory ships entered service, none was sunk by U-boats. Three were sunk due to Japanese action in the Pacific war. Cargo ships were converted to troop ships to bring US soldiers home at the end of World War II as part of Operation Magic Carpet. A total of 97 Victory ships were converted to carry up to 1600 soldiers, to convert the ships the cargo holds were converted with bunk beds, hammocks, mess halls and exercise places.

After the war many were sold and became commercial cargo ships and a few even became commercial passenger ships.

Empire Ships

The prefix "Empire" was adopted for the names of all merchant ships built in Britain for the British government in the Second world war.

This was a recognition that it was not just Great Britain that was fighting for the allies but every nation within the empire. It was also a useful means of distinguishing between the British government standard shipping of the Great War, which had the prefix "War", and the newer ships. In all, about 1,300 ships carried the Empire name.

The Ministry of War Transport was established on the 1st of May 1941 by merging the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Shipping, which was hoped would better coordinate transport activities.

At the admiralties behest, ship builders that had focused on tramp steamers formulated several partly pre-fabricated designs that were further refined into standard cargo ships of the B, C, D and Y types.

A boat or ship engaged in the tramp trade is one which does not have a fixed schedule, itinerary nor published ports of call, and trades on the spot market as opposed to freight liners. A steamship engaged in the tramp trade is sometimes called a tramp steamer; similar terms, such as tramp freighter and tramper, are also used. Chartering is done chiefly on London, New York, and Singapore shipbroking exchanges. The Baltic Exchange serves as a type of stock market index for the trade.

These ranged in size from 7,000 tons upwards. The Great War approach of imposing standard designs on shipbuilders was deliberately spurned, instead each yard was given its head in the conception that it would raise productivity by concentrating on what it did best. As a rule British shipbuilders in World War II constructed ships with which they were already accustomed to in the manner that it felt most comfortable.

One of the major issues that the British shipbuilding industry had to address was engine building capacity. At the start of the Great War, Britain had the annual capacity produce 1,400,000 hp. By the 1920's it had peaked at 1,800,000 hp and thereafter declined through the years of the recession to just 600,000 hp by the start of World War II.

A considerable increase in building capacity was clearly required, particularly as most of the existing production facilities were in the ship yards themselves and hence were already suffering from congestion.

So what were the B, C, D and white type standard ships and what happened to the A type.

Plans were in fact drawn up for the A type standard cargo ship by the early part of 1941, following a survey of selected prototype ships and based around a length of approximately 425 feet and a breadth of 56 feet. These ships were to be constructed using large pre-fabricated units which were then bought together on the slipway. An issue was that only a few shipyards would be capable of handling the largest of these units.

This was the downfall of the class A vessels. It was realised this approach would be unreasonably restrictive given the numbers that were required to be produced. Consequently the class A was reworked into the class B, which were essentially identical, but the prefabricated components were much smaller and consequently more yards could handle their construction.

They had a split superstructure with a hatch between the bridge and the funnel and were typically of around 7,000 Gross Registered Tons (GRT). Their triple expansion steam engines were intended to provide a service speed of 11.5 kn. The Y type was similar except the funnel and the kingposts ,serving number three hold in the split superstructure, were closer together then in the B type.

The amount of welding used in the construction of the ships was determined by the yards abilities. Each builder was allowed a certain level of variation to the basic design. But common to all where the engine, their component parts and the many fittings. All were mass produced to common specifications and delivered complete to the shipyards in the order required for their assembly into the ship. This required careful planning, timing and production control, especially after ships were launched and we're at the fitting out stage.

During the course of the war it was realised that there was a need for larger hatchways and better cargo handling gear. In 1942 the C type was designed to fulfil this need, not only with larger hatches giving better hold accessibility but with heavier derricks. This rig consisted of a 50 ton derrick, a 30 ton derrick, five 10 ton and five 5 ton derricks. The B type only had one 30 ton derrick, two 10 ton and eight 5 ton derricks. The D class vessels were simply a minor modification to the C class design. Both C and D class were again of approximately 7000 tons GRT.

Not all of the Empire vessels were built to the standardised designs, with numerous sub classes being produced. For example a need for fast cargo liners was identified in 1943, which resulted in a modification to the design to fulfil that requirement. This resulted in a 13 strong class capable of 15 knots, while displacing about 9,900 tons. Additionally the same design was used to produce nine fast cargo liner type ships as refrigerated ships. They each had 7,100 cubic meters of refrigerated storage. Despite this there was a permanent shortage of such capacity during the war which hampered the allies supply efforts as we will see later.

One of the more persistent of issues being encountered with supply delivery was a lack of heavy cargo lift capacity at smaller ports. To address this a small central engined ship was designed with a deadweight capacity of 4700 tonnes. These vessels were capable of mounting heavy lift gear, generally one 180 ton and one 150 ton crane. When they were deployed overseas they acted as tenders to other ships which otherwise would have waited for an available heavy lift crane birth. A total of 38 of these small vessels were completed. These vessels were particularly valuable for supplying Allied troops with the stores during Operation Overlord. A further 42 vessels were built in Canada to the same design but given Park names and registered in the Canadian Maritime registry.

Ocean type tankers.

As the war progressed, the realisation that there was a lack of tanker capacity, not just for oil products but other liquid products became clear. This resulted in the "Ocean" class tankers, which were sometimes known as the "3 12's" type. They got this name from being 12,000 tons deadweight with the speed of around 12 kn and a fuel consumption of 12 tonnes per day.

They in turn were replaced in production by the Norwegian type tankers which were slightly larger at 14,500 tonnes. The first of this class were fitted with 3800 hp triple expansion steam engines, these were later replaced by 3,300 hp diesel engines and in 1945 further upgraded to 4,000 hp diesel engines.

These, in turn, were replaced by the "Wave" class tankers which were produced from 1943 onwards with a speed of 15 kn which enabled these fast tankers to operate outside of the convoy system.

A further small class of 14 tankers were constructed from 1943 onwards, specifically to support the Allied Forces on the continent during Operation Overlord. They comprised ten 5000 ton capacity motor tankers, known as the intermediate type and four smaller ships of the "Empire Plim" type.

Empire F class coasters.

The "Empire F" class coasters were a small class of 38 vessels with a gross tonnage of 410 tons. The hull was the same as the small coastal tanker series despite being a completely separate class from the tankers.

They were extensively used during Operation Overlord as they were able to enter the small French Brittany ports.

Coastal tankers. CHANT class

The CHANT (from CHANnel Tanker) was a type of prefabricated coastal tanker that were built in the UK during the Second world war, due to the need for coastal tankers, particularly during Operation Overlord.

The CHANT were developed with the experience gained by building the TID class of inshore tugs. The TID were a class of 182 tugs built to a standard design. The CHANT were built from prefabricated sections that were manufactured at various factories across the UK. A total of 28 sections were joined together to make each ship. The largest sections weigh 13 tons, which enabled them to be delivered by road. To simplify construction they were built without compound curves or plates being either flat or curved in one direction only. All joints were welded with the final 10 inches being left unwelded at the factory to enable adjustments to the joints when the ship was assembled at the shipyard.

They were constructed with a flat bottom to enable them to ground on beaches while a double hull was used to minimise the chance of any leakage. Each CHANT was further subdivided into four tanks with a small circular hatch to allow the tanker to carry bulk oil. This was mounted in the centre of a large rectangular hatch which was used when the oil was in cans (known as packaged fuel.). A single mast with two derricks and winches was used to the loading and unloading of packaged products. The vessels were fitted with either 220 or 270 hp engines, giving a maximum speed of 7.5 kn, which was thought to be adequate because they were only intended for crossing the English Channel between Southern England and the French beaches. A total of 43 CHANTS were assembled at five different shipyards, all being launched by May 1944.

The CHANTS had known stability problems which required them to be kept in some ballast at all times, at least three were lost due to capsising doing the D-Day landings.

CHANTS were built to provide supplies of fuel to the allied Forces in the aftermath of D-Day. Five CHANTS were lost during June 1944, after which it was decided the vessels were only to be unloaded within the protection of a Mulberry harbour. CHANT 26 was driven ashore during the storms which destroyed the Mulberry Harbour and ended up in a field having passed through a hedge. After discharging her cargo, she was dragged back to the beach, refloated and returned to the UK.

Canada's contribution.

The Fort class.

The Fort ships were a class of 198 cargo ships built in Canada, during World War II, for use by the United Kingdom. They all had names prefix with "Fort" when built. The ships had long service lives entering Service in 1942 and with the last coming out of service in 1985. A total of 53 were lost during the war due to accident or enemy action.

All "Fort"" ships were owned by the British government. The "Fort" ships were 130 m long with a beam of 17 m, they were of approximately 7,100 gross registered tons. The ships were of three types, the "North Sand" type were of riveted construction while the "Canadian" and "Victory" types were of welded construction. They were built by 18 different Canadian shipyards, with their triple expansion steam engines being built by seven different Canadian manufacturers.

The Park class.

The Park class ships were constructed in Canada for Canada's merchant Navy. Park ships were built and operated by the Canadian government and where the equivalent to the Fort ships built in Canada and operated by the British government.

The Park Steamship Company was created by the Canadian government on April 8, 1942 to oversea the construction of merchant vessels to help replace lost vessels and administer the movement of material. This was part of a coordinated Allied effort that saw the construction of British, American and Canadian merchant ships using a common class of vessels.

Over the next three years the company ordered approximately 160 bulk cargo ships and 20 tankers. They were all to fly the Canadian flag. The ships at 10,100 ton deadweight were known as Park ships, named after Canadian parks. Forty Three smaller vessels at 4,100 tonnes were at first designated the "Grey" class, but they were later renamed to Park ships as well and were commonly known as the "Small Park". All the Park ships were powered by coal driven steam turbines. At the same time Canada produced 90 additional vessels for the American government, which in turn were turned over to the British merchant Navy under lend lease arrangements. They were built to the same design but were designed to burn oil instead of coal. These were the Fort ships as identified above.

So this gives us a very rapid and condensed view of the ships used to transport the material for Operation Overlord across the Atlantic. With a side quest to talk about coastal tankers and coastal freighters.

Next week we'll start discussing how the convoy was actually organised and talk about some examples of them.

Hope to see you then.

Great series. I never knew about the Canadian contribution here.